Reprinted Ford’s High Plains Drifter photo yesterday. Now, it’s just how I imagined it. Original, washed-out version here.

Category Archives: Uncategorized

Erratics and Invasives

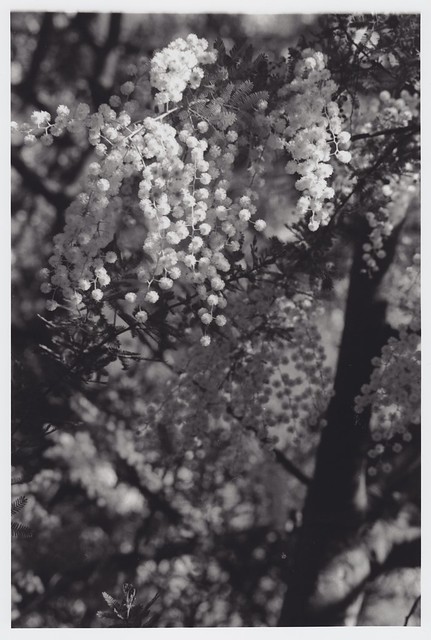

Acacia flowers. A tree in our back yard, next to the tree house in an olive tree. On the acacia:

For the same reasons it is favored as an erosion-control plant, with its easy spreading and resilience, some varieties of acacia, are potentially an invasive species. One of the most globally significant invasive Acacias is black wattle Acacia mearnsii, which is taking over grasslands and abandoned agricultural areas worldwide, especially in moderate coastal and island regions where mild climate promotes its spread. Australian/New Zealand Weed Risk Assessment gives it a “high risk, score of 15” rating and it is considered one of the world’s 100 most invasive species.[24] Extensive ecological studies should be performed before further introduction of acacia varieties as this fast-growing Genus, once introduced, spreads fast and is extremely difficult to eradicate.

Earlier this week I was inspired by a blog I discovered which includes a compilation of what the artist calls Erratics and Invasives–Glacial erratics, invasive species, and other erratic and invasive things. A simple concept. Pictures of rocks carried by glaciers throughout North America and invasive plants. Things that are just out of place. It really clicked with me as it’s in the same vein as what I’ve been experiencing lately. Specifically, we’ve visited many interesting geological sites, studied them, and also learned about the plant species in the area, often seeing things that aren’t supposed to be there, if that’s even possible.

I’m particularly interested and inspired by geology due to the vast time scale represented. Time too big to comprehend. Throw in things like unconformities and erratics and it’s like salt and pepper on a juicy steak–it gets more interesting. I can’t count the number of times I’ve encountered a boulder that just didn’t fit the scene. I’d stop, look around and see there’s no other thing like it nearby, and ask myself, how the hell did this get here? As a kid in Wyoming, I’ve seen plenty of this. Now, such experiences are even more interesting because I’ve the maturity to know the value of the pause involved when hit with these discoveries: It’s a moment to stop and think about just how short our time is here in relation to all that’s happened before we existed. A boulder that traveled sometimes hundreds of miles on a sheet of ice, thousands, if not millions, of years ago, only to land here of all places? And, it was just waiting here to be seen by me? Right now? Surrounded by shitty shopping malls and mouth breathing motorists? It’s enough to turn one into a solipsist.

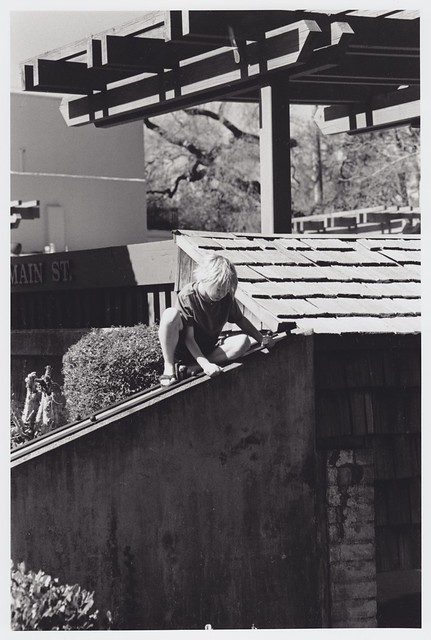

As mentioned in an earlier post, this weekend was beautiful. Amazing weather enabling us to hang out in the tree house and work in the yard. Here Jolene adds some sparkle to said tree house:

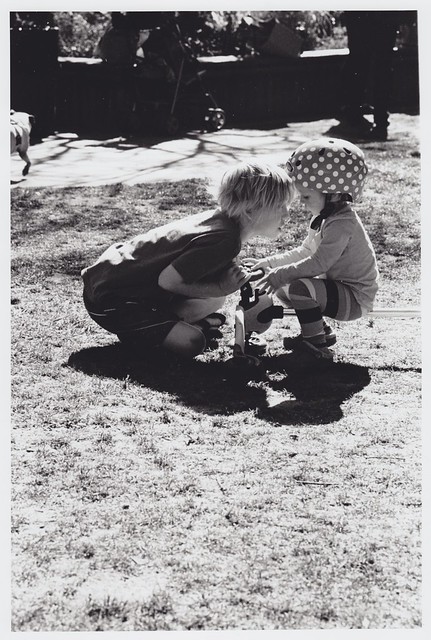

We originally planned to head up to the mountains, but the masses cut us off, taking up all possible places to stay. We didn’t plan ahead. Second choice was to visit the Western Pinnacles–the other side of Pinnacles we haven’t seen. However, we became distracted and had other work to finish first. Not enough time. Instead, we took moments here and there to enjoy a great morning, have a good breakfast at the Southern Kitchen in Los Gatos, and play in the park.

We originally planned to head up to the mountains, but the masses cut us off, taking up all possible places to stay. We didn’t plan ahead. Second choice was to visit the Western Pinnacles–the other side of Pinnacles we haven’t seen. However, we became distracted and had other work to finish first. Not enough time. Instead, we took moments here and there to enjoy a great morning, have a good breakfast at the Southern Kitchen in Los Gatos, and play in the park.

Chas downtown: “Jolene, are you listening?”

And, on the walk home, Chas takes every detour possible:

And, on the walk home, Chas takes every detour possible:

There will be time for another day out in the countryside, scanning for erratics, and in the meantime, there are plenty of invasives around to catch our attention.

There will be time for another day out in the countryside, scanning for erratics, and in the meantime, there are plenty of invasives around to catch our attention.

Nummy Lift

Last run of the day at Badger Pass. Chas, behind his board, is making and hoarding a battery of snowballs in preparation for Ford’s arrival off the bunny slope under the Bruin lift. Chas refused to eat all day due to excitement. So, he was punchy as hell. On this day, both boys learned to snowboard in under two hours–now they take the lift on their own and make it down the hill without falling. Not bad.

Jolene hit her wall and dropped her boot to get some end-of-day nummy. There was nobody around to bother us, so Steph plopped down on the bench under the running lift. We had several minutes to ourselves before Ford arrived to receive Chas’ surprise attack–a success.

The history of winter sports in Yosemite National Park is unique. Following the building of the Ahwahnee Hotel in 1925–1927,[4] came Yosemite’s first ski school in 1928 with Jules Fritsch as instructor.[5] Fritsch, a Swiss ski expert was part of a trained staff of winter sports experts available in Yosemite. Fritsch and the staff led six day snow excursions in Yosemite from the Ahwahnee to Tenaya Lake to bolster the ski school. Many believe this ski school was the first in California. In conjunction with the Curry Company, one of the first projects was the 1927 construction of a four-track toboggan slide near Camp Curry. Dr. Donald Tresidder, the first president the Yosemite Park & Curry Company and its guiding force, saw the visitor interest in winter sports and immediately formed the Yosemite Winter Club.[6] With the club’s enthusiast support, a small ski hill and ski jump near Tenaya Creek Bridge was built in 1928.[7]

Absorbing 10 Million Years

The boys take a few minutes from scrambling talus to warm themselves in the glow of 10 million years of batholithic uplift. We arrived the previous evening with just enough time to hike up to one of the ephemeral waterfalls near Yosemite’s entrance, but they couldn’t keep up with me when I climbed up to the base of the falls. At the the lower Yosemite Falls above, they were able to get much closer. Close enough to scare the tourists.

When I saw the boys lounging on the rocks while everyone was sweating bullets watching them (seriously, people need to get out more), I snapped the photo, turned to Steph, and said “that photo just made the trip for me.”

Starting 10 million years ago, vertical movement along the Sierra fault started to uplift the Sierra Nevada. Subsequent tilting of the Sierra block and the resulting accelerated uplift of the Sierra Nevada increased the gradient of western-flowing streams.[54] The streams consequently ran faster and thus cut their valleys more quickly. Additional uplift occurred when major faults developed to the east, especially the creation of Owens Valley from Basin and Range-associated extensional forces. Uplift of the Sierra accelerated again about two million years ago during the Pleistocene.

The uplifting and increased erosion exposed granitic rocks in the area to surface pressures, resulting in exfoliation (responsible for the rounded shape of the many domes in the park) and mass wasting following the numerous fracture joint planes (cracks; especially vertical ones) in the now solidified plutons.[41] Pleistocene glaciers further accelerated this process and the larger ones transported the resulting talus and till from valley floors.

Numerous vertical joint planes controlled where and how fast erosion took place. Most of these long, linear and very deep cracks trend northeast or northwest and form parallel, often regularly spaced sets. They were created by uplift-associated pressure release and by the unloading of overlying rock via erosion.