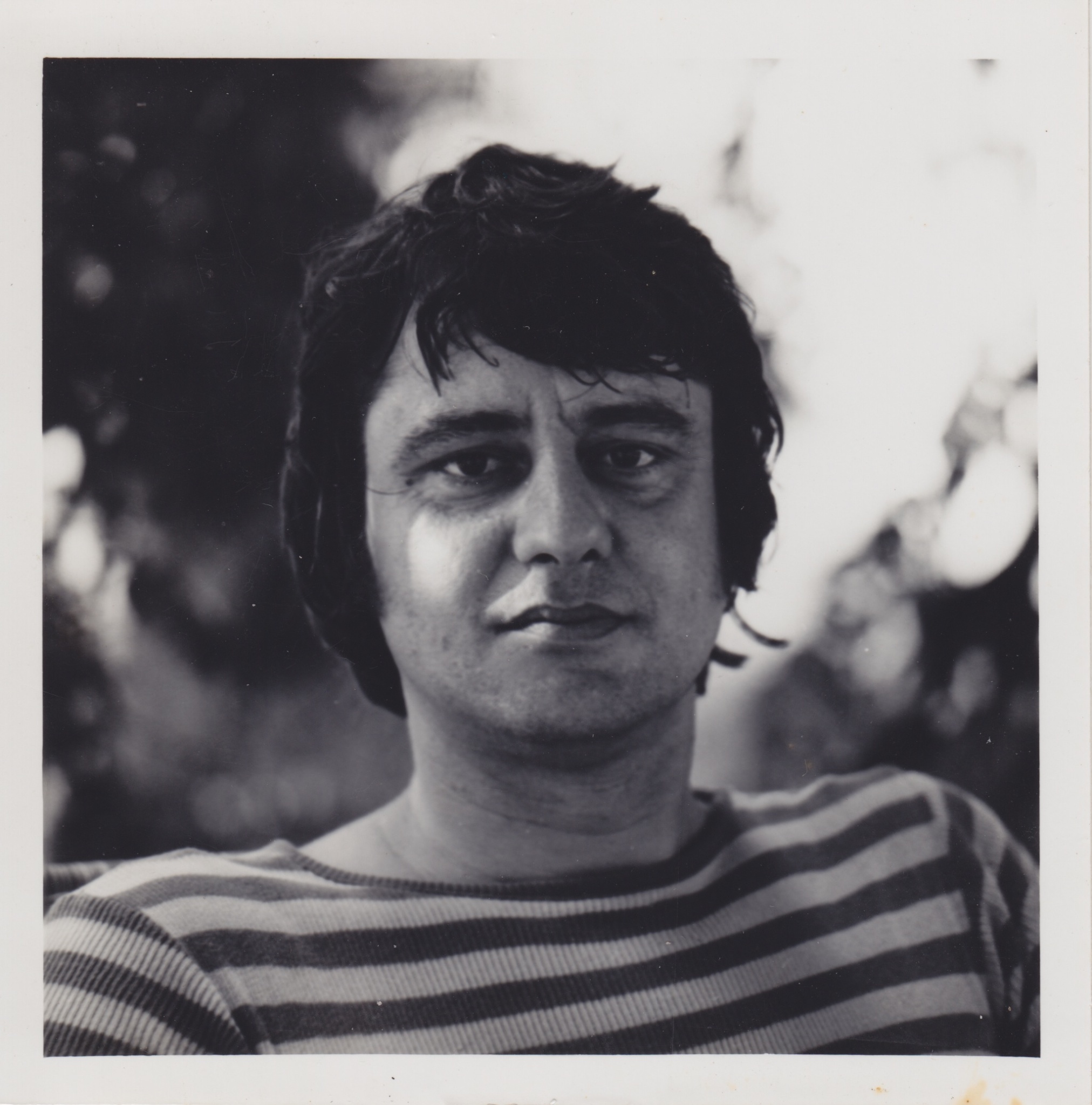

Howard Joseph Sicore 1940-2014

My father’s father was always a painful subject, but he brings him up as we enter a room of brown chairs filled with despair.

‘My dad never taught me anything.’

He describes how alcohol ruined his family. That Roger, his brother three years younger, was his father’s favorite.

‘Always gave him things like cars.’

A woman interrupts to ask something, but before she can finish he blurts, ‘Howard Sicore. Seven. Twenty-one. Forty.’

He’s receiving drips while sitting in a repulsive brown chair like those found in a delivery room for the husband to sleep, a recliner, with a side table for coffee.

‘These are all good people here.’

Everyone laughs. A man is wheeling over his tri-mix of drips to grab a couple of bags of free potato chips. Howard interrupts him.

‘Having fun yet?’

‘It is what it is.’ Says the stranger.

My father smiles and returns to his normal state of introspection.

‘I’ve a log cabin in mind, and someday it will be real. And a 1937 Ford two-door sedan. A kind of red. Tinted rear windows. In my three-car garage. Two stories. Bedroom, bathroom upstairs. If I can get this floor covering project going. I’ll keep investing more and more from the sales.’ He pauses, characteristically rubs his chest, sighs and looks down. ‘Just dreams that I have. You just don’t know if it will work or not, you know?’

He acts immortal. I’m just listening.

‘It’s nice to have dreams. It’s fun to think about things.’

He talks of his hair and concedes it’s time to get a haircut. Later in the day he will walk into a beauty school, where the young women there will treat him with dignity as they trim off all that remains, a few half-grey finger-sized strands of hair, and his sparse beard, down to stubble. When he stands to walk out of the salon, he looks just like his father. I do not tell him this.

‘I met your mom in a pool hall. The Blue Boar. I was friends with this heavy set guy, but he got mad at me because I talked to her first.’

He describes their circle of friends during their dating years. There was Pat Rogers in Fort Worth. And Jim and Carolyn. His brief descriptions of them leave more questions than answers.

‘I don’t know why she said this, but Carolyn said his penis was too small. Can you believe that?’

‘Jim’s?’

‘Yes!’

He is enjoying this.

‘I met your mom, and we’d gone over to my apartment. It was the first time that I kissed her. I just turned around, and I held her, and I asked her, ”May I kiss you?” And she let me. Ask her about that.’

This is one of his most valued memories. He is genuinely happy.

The subject returns to his brother.

‘Roger turned gay. When we were kids. I found them alone by the Santa Anna river. Well, I won’t say any more. George Herman. That’s who he was with.’

He says he never told anyone this happened. He protected his brother.

Happy birthday, Dad. I miss you.