Our plan was simple: Picnic and let the kids run amok in the talus and scree for hours, allowing them to find their own spaces for play, with eventual exhaustion. After the cave exit, the reservoir presents itself–a perfect place to picnic and explore. We spread the blanket, ate all the cucumbers, and Chas powered through yet another burrito (utilizing a fine Chas Pattern instance).

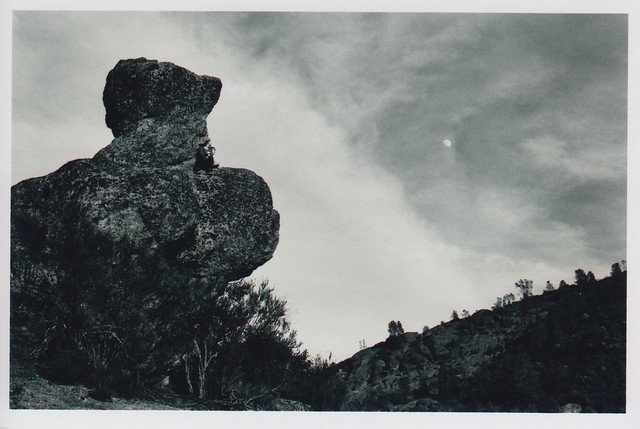

Then we split up. I grabbed my tripod and a few rolls of 50 and 100. The boys headed to the reservoir, and Jolene climbed about. Eventually, I headed up the cliffs, and the boys seemed to follow, each finding their own way towards me. I captured many great views, and I’ll share a few. Here’s one of my favorites where Chas climbed a deceivingly tall rhyolite formation, Paloma followed, and I scrambled up below to align them with the Moon. Glad I did.

On rhyolite:

Rhyolite can be considered as the extrusive equivalent to the plutonic granite rock, and consequently, outcrops of rhyolite may bear a resemblance to granite. Due to their high content of silica and low iron and magnesium contents, rhyolite melts are highly polymerized and form highly viscous lavas. They can also occur as breccias or in volcanic plugs and dikes. Rhyolites that cool too quickly to grow crystals form a natural glass or vitrophyre, also called obsidian. Slower cooling forms microscopic crystals in the lava and results in textures such as flow foliations, spherulitic, nodular, and lithophysal structures. Some rhyolite is highly vesicularpumice. Many eruptions of rhyolite are highly explosive and the deposits may consist of fallout tephra/tuff or of ignimbrites.